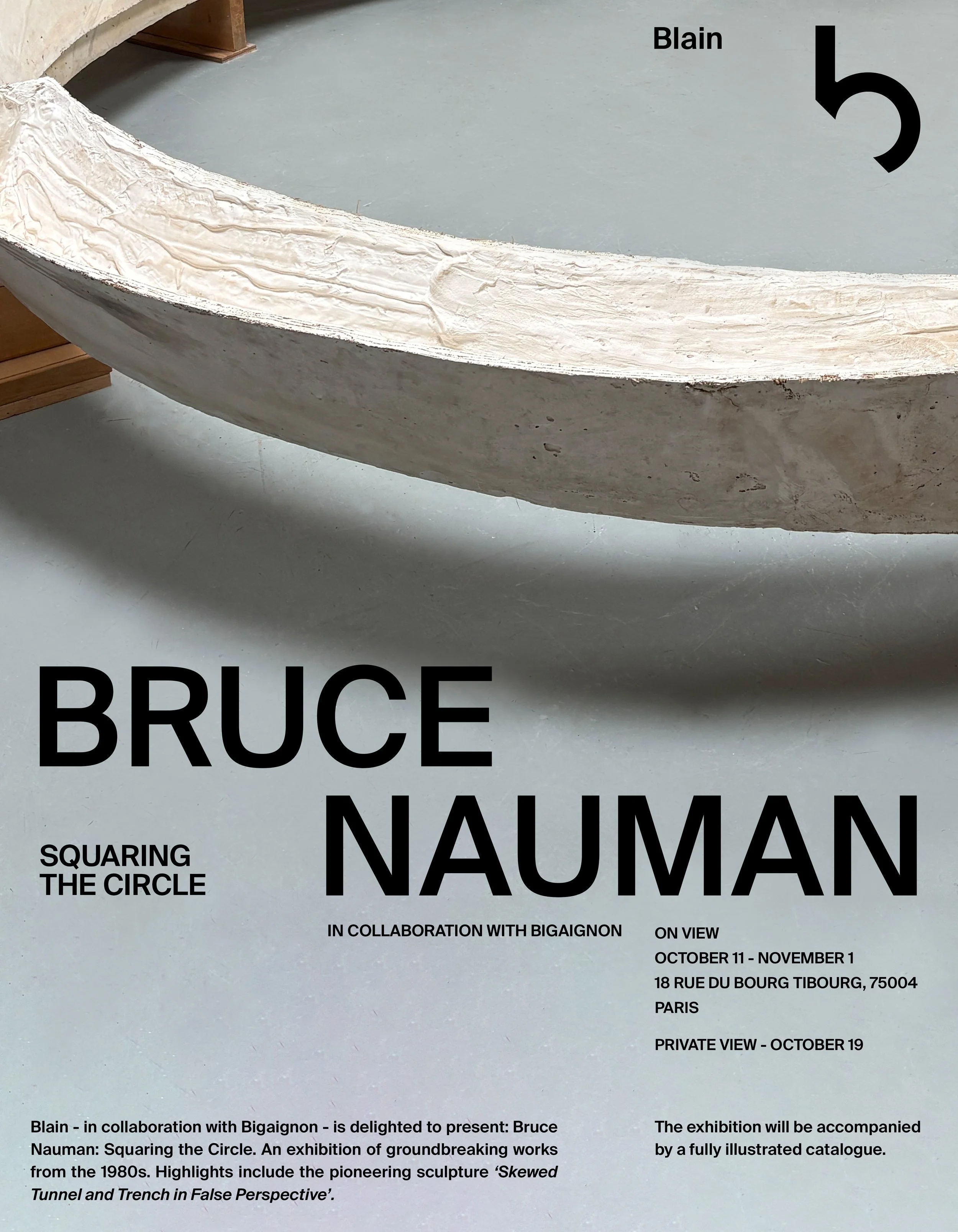

BRUCE NAUMAN • SQUARING THE CIRCLE

PREVIEW FROM SATURDAY 11 OCTOBER 2025

OPENING ON THURSDAY 16 OCTOBER 2025 (6-9PM)

SPECIAL “STARTING SUNDAY”: SUNDAY 19 OCTOBER 2025 (2-6PM)

EXHIBITION FROM 11 OCTOBER TO 1ST NOVEMBER 2025

Blain - in collaboration with Bigaignon - is delighted to present: Bruce Nauman: Squaring the Circle: an exhibition exploring the significance of conceptual mathematics for the artist’s pioneering practice through a tightly angled focus on a select group of his most groundbreaking works from the 1980s.

Central to the exhibition is the iconic sculpture: ‘Skewed Tunnel and Trench in False Perspective’ (1981) - an important example from the models for underground tunnels that the artist created between 1977 and 1981 (two sister works in this series: ‘Smoke Rings’ (Model for Underground Tunnels),(1979) and ‘Untitled’ (Model for Trench, Shaft, and Tunnel),(1978), are in the Centre de Pompidou and Reina Sofia Collections, respectively). No less important and strategically positioned to create a strong dialogue with the tunnel sculpture, are two monumental works on paper: ‘Buried Ring’ (1981), ‘Untitled (Study for Sculpture) (1983), and the seminal drawing: ‘4 Directions In & Out’ (1985).

The intimate nature of the exhibition space affords the viewer a rare opportunity to engage with some of Nauman’s most profound and thought-provoking work in a context that is both focused and devoid of distractions. Nauman is known for drawing attention to themes of awareness, control and confinement in his practice and for seeking to provoke physical and emotional responses in his audience. The viewer’s experience of space is therefore crucial to their engagement with Nauman’s work.

Long considered one of the most innovative, influential and challenging artists of his generation, Nauman’s work eludes easy definition - partly because he has chosen to work across a diverse array of mediums throughout his career - and because he has also resisted limiting himself to any one particular style. Curator and leading authority on Nauman, Kathy Halbreich argues: ‘The fluidity of his ideas, approaches, and materials makes the most primitive of critical acts - that of labelling - a fleeting and not terribly potent practice. He is impossible to pin down.’

This should not necessarily be taken as the artist’s attempt to avoid categorisation, rather that his practice could be described more accurately as mathematical concepts in disguise. We should not be surprised by this, given that Nauman initially studied mathematics and physics at university before deciding to focus on art. He himself acknowledges that (though) ‘I didn’t become a mathematician. I think there was a certain thinking process which was very similar and which carried over into art. This investigative activity is necessary.’

Nauman’s use of systems, repetition and spatial arrangements could be regarded as reappropriating mathematical ideas in a conceptual way. This is evident in the artist’s tunnel models and ambitious drawings that evoke liminal realms and challenge the viewer’s notions of perception and the reality of their own physical experience.

Also apparent is how Nauman balanced the starkly minimalist aesthetic which dominated western art in the 1970s and 80s, with the tactile nature of the humble materials he chose to employ. By deliberately veering away from metal - such as Alexander Calder and Donald Judd favoured, and eschewing stone for plaster, Nauman plunged into uncharted waters. The artist allowed imperfections from the casting process to remain in the plaster’s form. These gritty elements are in direct contradiction to the pristine nature of Minimalism’s perfect surfaces: he was pioneering.

Besides the formal differences between Nauman and fellow sculptors of the time who sought to control their materials entirely, there is a conceptual distinction which Nauman also seems to be making - this is evinced by ‘Skewed Tunnel and Trench in False Perspective’, as the two halves of Nauman’s circle never quite meet up. This means that if one was to walk the trench, it would be impossible to complete its arc without first reaching a dead end. The circle is therefore not perfect and Nauman’s impossible tunnels have been rendered - deliberately - without entrance or exit.

During this period, Nauman continued to research and create mathematical forms such as circles, triangles, squares - often intersecting half parts of these shapes in order to forge a new form. His models for underground tunnels became a consuming focus. The artist wanted the ‘model tunnels’ to be without place - possibly buried, floating in an indeterminate space and roughly constructed from materials lying around in his studio.

The artist’s inventiveness with cast off materials recalls Picasso’s impressive ability to reappropriate from his surroundings, but Nauman’s ambitious drawings from this period - which are clearly designed as a means of developing new methods of construction and presentation - taken along with his tunnel sculptures - may also have been inspired by Henry Moore’s tunnel drawings from WWII.

In an interview with Joan Simon for Art in America (1988), Nauman was asked whether his interest in inverting ideas and showing ‘what’s “not there,” and in solving - or at least revealing “impossible” problems related in part to his training as a mathematician. Nauman replied by stating that he was especially interested in how one could turn that logic inside out. He was fascinated by mathematical problems, particularly “squaring the circle” (where for hundreds of years mathematicians tried to find a geometrical way of finding a square equal in area to a circle. It took until the 19th century for it to be proved that this cannot be done. Nauman comments: ‘I can’t remember (the mathematician’s), name, (but), his approach was to step outside the problem, rather than struggling inside the problem… Standing outside and looking at how something gets done, or doesn’t get done, is really fascinating and curious, if I can manage to get outside of a problem…and watch myself having a hard time, then I can see what I’m going to do - it makes it possible. It works.’

In 1979, Bruce Nauman moved to Pecos, New Mexico, where he built a new studio space. The tunnel projects were amongst the first objects Nauman created in this new studio. Nauman imagined endless hallways of curving, twisting forms that would mostly be buried underground - though some were conceived to float in the sky. The artist was particularly drawn to the physical experience of walking through a tunnel and the creeping sense of disorientation that occurs when rounding the corner and confronting the unknown. In a circular tunnel, one would continually follow its curving form, never sure as to what lurked just around the bend. He explained: ‘because it’s a circle and you walk around a circle, you never will really see very far behind you—you are unable to even get outside the piece...’ (B. Nauman, quoted in M. de Angelus, “Interview with Bruce Nauman,” 1980, J. Kraynak, ed., Please Pay Attention Please: Bruce Nauman’s Words, Cambridge, 2003, p. 280).

Upon seeing Nauman’s work at the Halle für Neue Kunst in Schaffhausen, Switzerland in the 1980s, the curator Richard Flood remarked: ‘Here was the spine of American art. I got kicked in the stomach. The way you are asked to physicalise yourself in relation to the work really knocked me out.’ Flood included Skewed Tunnel and Trench in False Perspective in the exhibition he curated at Barbara Gladstone Gallery in New York in 1987. He described the sensation: ‘I didn’t understand these pieces at first. But a few years later, it looked as if it had been unearthed and was waiting for time to catch up with it.’ (R. Flood, quoted in B. Adams, “The Nauman Phenomenon,” R. C. Morgan, ed., Bruce Nauman: Art and Performance, Baltimore & London, 2002, p. 82).

As humans, we perceive time as linear. It is a rare thing if we can try and step outside it for a moment. If we could, then perhaps we would better understand those figures in history who were ahead of the curve. Nauman is one such example. His ability to step outside of himself and observe his own ideas surely enabled him to find a window into art’s future - while he waited for the rest of the world to catch up.